Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in December 2019, many hypotheses have been advanced to explain where the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) actually came from. Initial reports pointed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, China, as the source of infection, however later studies called this into question. Given the uncertainty, many have suggested that a laboratory in Wuhan may be the actual source of the novel coronavirus. In this Insight article, we examine the three most widespread origin stories for the novel coronavirus, and examine the evidence for or against each proposed hypothesis. The hypotheses are listed in order from least likely to most likely, based on currently available evidence.

Although none of the individual pieces of evidence described below definitively identify the virus’ origin, the preponderance of evidence when taken together currently points to a natural origin with a subsequent zoonotic transmission from animals to humans, rather than a bioengineering or lab leak origin.

Contents

- Hypothesis 1: The novel coronavirus is manmade, genetically engineered as bioweaponry or for health applications

- Hypothesis 2: The novel coronavirus is a natural virus that was being studied in the lab, from which it was accidentally or deliberately released

- Hypothesis 3: The novel coronavirus evolved naturally and the outbreak began through zoonotic infection

- Conclusions

- References

Hypothesis 1: The novel coronavirus is manmade, genetically engineered as bioweaponry or for health applications

This hypothesis began circulating in February 2020. To date, it has been largely rejected by the scientific community. Some of the early claims have their roots in a preprint (a study in progress which has not been peer-reviewed or formally published) uploaded to ResearchGate by Chinese scientists Botao Xiao and Lei Xiao, who claimed that “somebody was entangled with the evolution of 2019-nCoV coronavirus. In addition to origins of natural recombination and intermediate host, the killer coronavirus probably originated from a laboratory in Wuhan”.

However, the only piece of evidence the authors provided to support their conclusion was the proximity of both the Wuhan Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) to the seafood market. The authors later withdrew their article, saying that their speculation about the possible origins “was not supported by direct proofs.” Copies of the original article can still be found online.

The withdrawal of the preprint did not stop this hypothesis from spreading—instead it continued to grow in complexity, with some claiming that the virus showed signs of genetic engineering. Some of these claims were based on a preprint uploaded to BioRxiv, purporting to show that genetic material from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) had been inserted into the novel coronavirus.

This study was found to have significant flaws in design and execution and was also later withdrawn, as reported in our review explaining that “No, ‘HIV insertions’ were not identified in the 2019 coronavirus”. However, the poor quality of the preprint did not prevent this baseless speculation from being promoted by blogs such as Zero Hedge, Infowars, Natural News, and even some scientists like Luc Montagnier, a French virologist who co-discovered HIV, but has recently become a promoter of numerous unsupported theories.

Indeed, scientists who examined the preprint highlighted that these so-called insertions are very short genetic sequences which are also present in many other life forms, such as the bacterium Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum, the spider Araneus ventricosus, and the parasites Cryptosporidium and Plasmodium malariae, which cause cryptosporidiosis and malaria, respectively[1,2]. Trevor Bedford, virologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and professor at the University of Washington, explained on Twitter that “a simple BLAST of such short sequences shows [a] match to a huge variety of organisms. No reason to conclude HIV. […] These ‘inserts’ are nothing of the sort proposed by the paper and instead arose naturally in the ancestral bat virus.”

In other words, the sequences analyzed by the study authors were so short that it is easy to find similarities to a wide variety of organisms, including HIV. An analogy would be to search for a short and commonly-used word, like “sky”, in a search engine and claim that the search results show content that is identical or similar to each other solely because of that one word.

Another version of the engineered-virus story stated that a “pShuttle-SN” sequence is present in the novel coronavirus. The pShuttle-SN vector was used during efforts to develop candidates for a SARS vaccine[3] and was therefore used to support claims of human engineering. These claims appeared in blogs such as Infowars, Natural News, and The Epoch Times. However, analysis of the genomic sequence of the novel coronavirus showed that no such man-made sequence was present, as reported in our review.

Other claims regarding the purported manmade origins of the virus have linked it to bioweapons research. These have appeared in articles such as a 22 February 2020 story by the New York Post, which we also reviewed and scientists found to be of low scientific credibility. The article provided no evidence that the novel coronavirus is linked to bioweapons research.

On 17 March 2020, a group of scientists published findings from a genomic analysis of the novel coronavirus in Nature Medicine[4], which established that SARS-CoV-2 is of natural origin, likely originating in pangolins or bats (or both) and later developing the ability to infect humans. Their investigation focused mainly on the so-called spike (S) protein, which is located on the surface of the enveloping membrane of SARS-CoV-2. The S protein allows the virus to bind to and infect animal cells. After the 2003-2005 SARS outbreak, researchers identified a set of key amino acids within the S protein which give SARS-CoV-1 a super-affinity for the ACE2 target receptor located on the surface of human cells[5,6].

Surprisingly, the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 does not contain this optimal set of amino acids[4], yet is nonetheless able to bind ACE2 with a greater affinity than SARS-CoV-1[7]. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that SARS-CoV-2 evolved independently of human intervention and undermine the claim that it was manmade[1]. This is because if scientists had attempted to engineer improved ACE2 binding in a coronavirus, the best strategy would have been to harness the already-known and efficient amino acid sequences described in SARS-CoV-1 in order to produce a more optimal molecular design for SARS-CoV-2. The authors of the Nature Medicine study[4] concluded that “Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.”

In summary, the hypothesis that the virus is manmade or engineered in any way is unsupported and inconsistent with available evidence, leading Bedford to assess the probability of this hypothesis being correct as extremely unlikely. Kristian Andersen, professor at the Scripps in San Diego declared during an online seminar, “I know there has been a lot of talk about Chinese bioweapons, bioengineering, and engineering in general. All of that, I can say, is fully inconsistent with the data”.

Like Andersen, other scientists have repeatedly explained that there is no evidence to support the claim that the virus was human engineered. In a statement published on 19 February in The Lancet, 27 eminent public health scientists in the U.S., Europe, the U.K., Australia, and Asia cited numerous studies from multiple countries which “overwhelmingly conclude that this coronavirus originated in wildlife[8-15] as have so many other emerging pathogens.”

An announcement by the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence, published on 30 April 2020, echoes the conclusions of these scientists, stating that “The Intelligence Community also concurs with the wide scientific consensus that the COVID-19 virus was not manmade or genetically modified.”

Hypothesis 2: The novel coronavirus is a natural virus that was being studied in the lab, from which it was accidentally or deliberately released

Many have pointed out that even though the virus was unlikely engineered, it still might have been purposely or accidentally released from a lab. Claims about a possible laboratory release often point to a laboratory in China as the source, more specifically the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), given that one of its laboratories studies bat coronaviruses. Similarly speculative claims have also implicated laboratories in the U.S. and Canada.

However, there is no evidence in either scientific publications or public announcements indicating that a virus resembling SARS-CoV-2 had been studied or cultured in any lab prior to the outbreak. While this of course does not rule out the possibility that scientists were working on it in secret, as of today, this claim is speculative and unsupported by evidence.

A January 2020 study in The Lancet, which found that about one-third of the initial round of infections had no connection to the Huanan seafood market[15], has been suggested as evidence that the virus may have leaked from a nearby lab. Richard Ebright, a professor of chemical biology at Rutgers, said in this CNN article:

“It is absolutely clear the market had no connection with the origin of the outbreak virus, and, instead, only was involved in amplification of an outbreak that had started elsewhere in Wuhan almost a full month earlier.”

Ebright also told CNN that “The possibility that the virus entered humans through a laboratory accident cannot and should not be dismissed.”

Nikolai Petrovsky, a professor at Flinders University who specializes in vaccine development, also supported the hypothesis that the virus could have escaped from a lab. In this article, he stated that “no corresponding virus has been found to exist in nature” and cited as-yet unpublished work, saying that the hypothesis is “absolutely plausible”. Petrovsky suggested that the virus “could have escaped [the biosecure facility in Wuhan] either through accidental infection of a staff member who then visited the fish market several blocks away and there infected others, or by inappropriate disposal of waste from the facility that either infected humans outside the facility directly or via a susceptible vector such as a stray cat that then frequented the market and resulted in transmission there to humans.”

Some have argued that instead of originating in nature, the virus could have been generated through simulated evolution in the lab. Christian Stevens, from the Benhur Lee lab at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, explained in this article the extreme unlikelihood of this scenario.

Briefly, the mutations in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S protein in SARS-CoV-2 resemble that of some pangolin coronaviruses. These mutations are also what make SARS-CoV-2 much better at infecting humans compared to SARS-CoV-1. Such mutations could be evolved in the lab through simulated evolution, however the “likelihood of simulated natural selection stumbling on the near exact RBD from a previously unknown pangolin coronavirus is mathematically unlikely,” said Stevens.

Furthermore, scientists would have had to know about these mutations in the S protein of some pangolin coronaviruses before the outbreak, and then tried to evolve a bat coronavirus with the same characteristics through animal experiments. As these mutations in pangolin coronaviruses were not identified until after the outbreak[16], it does not make sense for scientists to have performed such experiments in the lab, as there would have been little to no scientific justification for doing so.

Other considerations are the polybasic cleavage site and the O-linked glycan additions to the S protein, which have not been identified in bat betacoronaviruses nor the pangolin betacoronaviruses sampled so far. However, evidence indicates that these features are much more likely to have arisen in the presence of an immune system, suggesting that this is a natural adaptation by the virus to a live host, either an animal or a human. Because lab-based cell cultures do not have immune systems, Stevens explained that it is extremely unlikely that the virus would have developed such features using cell culture approaches, thereby undermining the lab-generated claims that some have proposed.

What about using animal models for evolution, which would provide selective pressure from an immune system? Stevens also examined this possibility and concluded that “there is no known animal model that would allow for selection of human-like ACE2 binding and avoidance of immune recognition. This strongly suggests that SARS-CoV-2 could not have been developed in a lab, even by a system of simulated natural selection.”

In other words, the overall combination of features observed in SARS-CoV-2 is extremely unlikely to have arisen through experiments, even simulated evolution, because the experimental tools are not available at the moment.

Zhengli Shi, the head of the laboratory studying bat coronaviruses at the WIV, clarified in a Scientific American report published on 11 March, that during the early days of the outbreak, she had her team check the genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 against the bat coronavirus strains being studied in her lab to ensure that the outbreak had not resulted from “any mishandling of experimental materials, especially during disposal”. They found that “none of the sequences matched those of the viruses her team had sampled from bat caves.”

However, this testimony has not satisfied those who allege a cover-up of a lab accident due to inadequate biosecurity, intentional release, or plain carelessness. Recent opinion pieces published by the Washington Post—one on 2 April 2020 and another on 14 April 2020—have also fueled speculation that the virus was accidentally released from a laboratory at the WIV due to biosafety lapses reportedly documented in diplomatic cables from 2018. The authors of these opinion pieces were careful to distance themselves from earlier claims that the coronavirus was bioengineered or resulted from “deliberate wrongdoing”, as one author stated. In any event, the accidental release scenario is currently being considered by scientists and U.S. intelligence and national security officials.

Indeed, despite safeguards, laboratory accidents can and do occur, and some have even caused outbreaks. In 2007, an outbreak of foot and mouth disease (FMD) among livestock in the U.K. was linked to a faulty gas valve connected to labs involved in researching and producing HFM vaccines. And in 2004, a re-emergence of SARS occurred in Beijing, China, as a result of two lab accidents.

Scientists’ assessments of the likelihood of Hypothesis 2

In an article published on 6 April, experts expressed skepticism at the “lab leak” hypothesis. Vincent Racaniello, a professor of virology at Columbia University, said “I think it has no credibility.” And Simon Anthony, an assistant professor at Columbia who studies the ecology and evolution of viruses, stated, “it all feels far-fetched […] Lab accidents do happen, we know that, but […] there’s certainly no evidence to support that theory.”

In an April 10th article, Amesh Adalja from Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security stated that he thought the “lab leak” hypothesis had “a lower probability than the pure zoonotic theory. I think as we get a better understanding of where the origin of this virus was, and get closer to patient zero, that will explain some of the mystery.” Bill Hanage, associate professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said “If there is evidence to really support this theory beyond the coincidence of the location of the lab, then I haven’t seen it, and I don’t make decisions on the basis of coincidence.”

Several scientists have taken to Twitter to ponder the “lab leak” hypothesis made by the Washington Post opinion articles:

“Overall, we have virus group, molecular features, market association, and environmental samples all pointing strongly towards zoonosis. The location in Wuhan is the only thing at all suggestive of lab escape. I see strength of evidence entirely for zoonosis.”

“We don’t know how this virus emerged, but all evidence points to spillover from its natural reservoir, whether that be a bat or some other intermediate species, pangolins or otherwise. Pushing this unsupported ‘accident’ theory hinders efforts to actually determine virus origin.”

“The bottom line is that those vague diplomatic cables do not provide any specific information suggesting that [SARS-CoV-2] emerged from incompetence or poor biosafety protocols or anything else.”

—Angela Rasmussen [referencing the 14 April Washington Post opinion piece]

“Most likely either 1) virus evolved to its current pathogenic state via a non-human host and then jumped to humans, or 2) a non-pathogenic version of the virus jumped from an animal into humans then evolved to a pathogenic state.”

“All current data supports that the ancestral station strain of the virus is in bats—they serve as the zoonotic reservoir. Then a spillover event occured into humans, perhaps aided by another mammal, although that’s debatable.”

“There is strong evidence that the #SARSCoV2 #coronavirus is NOT an engineered bioweapon.

That said, it’s important to be upfront that we do not have sufficient evidence to exclude entirely the possibility that it escaped from a research lab doing gain of function experiments.”

In summary, the hypothesis that the virus escaped from a lab is supported largely by circumstantial evidence and is not supported by genomic analyses and publicly available information. In the absence of evidence for or against an accidental lab leak, one cannot rule it out as the actual source of the outbreak. “I don’t think we have real data to say when these things began, in large part because the data are being held back from inspection,” said Gerald Keusch, associate director of the Boston University National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories, in this LiveScience article.

Given allegations of a cover-up, it appears that only an open and transparent review of the laboratory activities at WIV can allow us to confirm or reject this unlikely hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: The novel coronavirus evolved naturally and the outbreak began through zoonotic infection

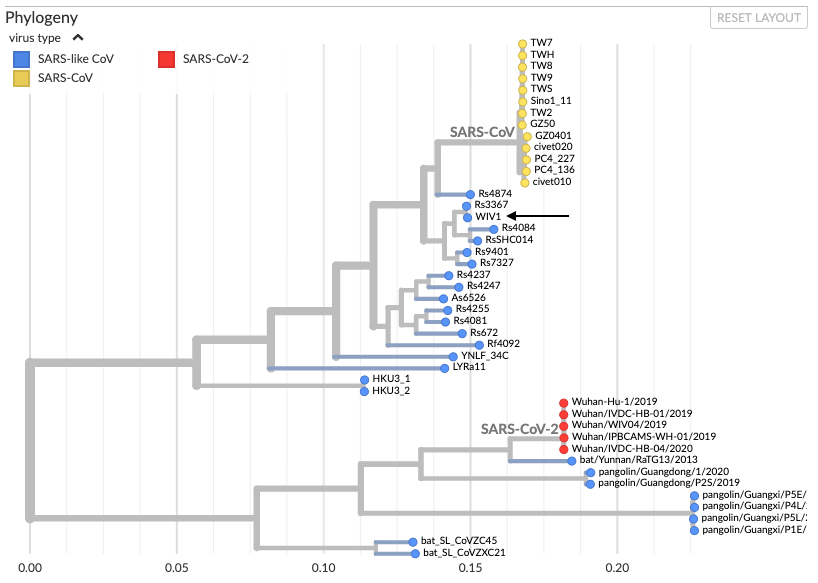

Virologists explain that the most likely hypothesis is that the outbreak started with a naturally-occurring zoonotic infection—one that is transmitted from animals to humans—rather than a lab breach. This is largely due to what we know of the virus’ genomic features, which strongly indicate a natural origin. For example, if a virus had escaped from a laboratory, its genome would likely be most similar to those of the viral strains cultured in that lab. However, as shown in this phylogenetic tree by Bedford (see figure below), SARS-CoV-2 does not cluster in the same branch as the SARS-like coronavirus WIV1 and SARS-CoV-1, which are commonly cultured lab strains with the closest similarity to SARS-CoV-2 at the WIV facility, which is the lab that some have suggested might be a potential source of a lab leak. Instead, SARS-CoV-2 aligns most closely with coronaviruses isolated in the wild from bats and pangolins, indicating that it is more likely to have come from a natural source than from a lab:

Figure—Phylogenetic tree showing evolutionary relationships between different coronaviruses—mostly bat coronaviruses and some pangolin coronaviruses (by Trevor Bedford). Different lab strains of SARS-CoV-1 (referred to as SARS-CoV here) are represented by yellow dots. WIV1, another common lab strain, is indicated with a black arrow.

Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 displays evolutionary features which suggest that the virus originated in animals and jumped to humans. The closest sequenced ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 is RaTG13, a bat coronavirus with about 96% genome sequence identity[8]. But SARS-CoV-2 also has features that distinguish it from RaTG13 and other SARS-like coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-1. As mentioned in the previous section, these features are: mutations in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S protein, a polybasic cleavage site, and a nearby O-linked glycan addition site in the S protein[4]. The mutations in the RBD of the S protein resemble those of some pangolin coronaviruses, suggesting that the virus made a jump from bats to an intermediate (perhaps pangolins), and then later to humans.

To briefly re-cap from the previous section discussing the hypothesis of a lab origin, Christian Stevens explained in this article that the polybasic cleavage site and the O-linked glycan additions to the S protein have not been identified in bat betacoronaviruses nor the pangolin betacoronaviruses sampled so far. However, evidence indicates that these features are much more likely to have arisen in the presence of an immune system, suggesting that this is a natural adaptation by the virus to a live host, either an animal or a human.

And again, “there is no known animal model that would allow for selection of human-like ACE2 binding and avoidance of immune recognition,” Stevens explained. “This strongly suggests that SARS-CoV-2 could not have been developed in a lab, even by a system of simulated natural selection.” In other words, the overall combination of features observed in SARS-CoV-2 is extremely unlikely to have arisen through experiments, even simulated evolution, because the experimental tools are not available at the moment.

Finally, Stevens highlighted that the Ka/Ks ratio of the virus strongly indicates that the virus did not come from lab-simulated evolution. The Ka/Ks ratio calculates the level of synonymous mutations (which do not produce any functional change in proteins) and non-synonymous mutations (which produce functional changes in proteins). Non-synonymous mutations are more likely to occur in the presence of selective pressure, such as a need to adapt to a new environment:

“Because synonymous mutations should have no effect, we expect them to happen at a relatively consistent rate. That makes them a good baseline that we can compare the number of non-synonymous mutations to. By calculating the ratio between these two numbers we can differentiate between three different types of selection:

- Purifying selection: This virus is already a great fit where it is and cannot afford to change because every change makes it worse. You should see very few non-synonymous changes here.

- Darwinian selection: This virus is not a good fit where it is and has to change and get better or it’s going to die out. You should see many non-synonymous changes.

- Neutral selection: There is no pressure on this virus either way. Non-synonymous changes and synonymous changes should come at about the same rate.

We would expect a virus that is learning to exist in a new context would be undergoing Darwinian selection and we would see a high rate of non-synonymous changes in some part of the genome. This would be the case if the virus were being designed via simulated natural selection, we would expect at least some part of the genome to show Darwinian selection.”

An analysis by Bedford demonstrates that the level of non-synonymous mutations between SARS-CoV-2 and the naturally occurring RaTG13 are highly similar, standing at 14.3% and 14.2%, respectively.

“Both of these numbers indicate a purifying selection, with very few non-synonymous changes. This holds true across the entire genome with no part of it showing Darwinian selection. This is a very strong indicator that SARS-CoV-2 was not designed using forced selection in a lab,” Stevens concluded.

Conclusions

Taken together, the information presented here suggests that it is much more likely that SARS-CoV-2 was generated naturally and transmitted zoonotically, without any engineering or lab growth. Especially given the fact that the prior probability for the zoonotic hypothesis is high. Indeed, zoonotic infections (transmission of pathogens from animals/insects to humans) are not only plausible but common throughout the world, and have also caused outbreaks in the past. For example, the SARS outbreak, which began in 2002, was linked to civet cats. Outbreaks of Middle East respiratory syndrome have been linked to contact with camels. Nipah virus infection has been linked to fruit bats and caused outbreaks in Asia. Mosquitoes transmit viruses such as Zika, dengue, and chikungunya, while ticks also carry a range of pathogens that cause illnesses such as Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. In fact, according to the World Health Organization, about 60% of emerging diseases are zoonotic infections.

In summary, the hypothesis that the virus escaped from a lab is supported largely by circumstantial evidence and is not supported by scientific studies and publicly available information. In the case of the hypothesis that the outbreak began with zoonotic infection, at the moment genomic analyses are consistent with a natural origin for the virus and support the idea that the outbreak began zoonotically. Unlike the manmade virus and lab escape hypotheses, there is no compelling evidence against the hypothesis for natural zoonosis. As Stevens concluded, the hypothesis for natural zoonosis is the one that fits all available evidence, is most parsimonious, and best satisfies the concept of Occam’s Razor—that the simplest solution is most likely the right one.

READ MORE

Christian Stevens from the Benhur Lee lab at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine has provided a comprehensive explanation of the multiple scientific studies examining the origin of the coronavirus.

Scientists explained in this 23 April NPR article why they found the lab accident hypothesis unlikely. In fact, the article states that “there is virtually no chance that the new coronavirus was released as result of a laboratory accident in China or anywhere else.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article has been reviewed for accuracy by Stanley Perlman, professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa.

UPDATE (4 May 2020):

An announcement on 30 April 2020 by the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence has stated that “The Intelligence Community also concurs with the wide scientific consensus that the COVID-19 virus was not manmade or genetically modified.”

REFERENCES

- 1 – Liu et al. (2020) No Credible Evidence Supporting Claims of the Laboratory Engineering of SARS-CoV-2. Emerging Microbes and Infections.

- 2 – Xiao et al. (2020) HIV-1 Did Not Contribute to the 2019-nCoV Genome. Emerging Microbes and Infections.

- 3 – Liu et al. (2005) Adenoviral expression of a truncated S1 subunit of SARS-CoV spike protein results in specific humoral immune responses against SARS-CoV in rats. Virus Research.

- 4 – Andersen et al. (2020) The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine.

- 5 – Wan et al. (2020) Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: an Analysis Based on Decade-Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus. Journal of Virology.

- 6 – Wu et al. (2012) Mechanisms of Host Receptor Adaptation by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Journal of Biological Chemistry.

- 7 – Wrapp et al. (2020) Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science.

- 8 – Zhou et al. (2020) A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature.

- 9 – Lu et al. (2020) Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The Lancet.

- 10 – Zhu et al. (2020) A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine.

- 11 – Ren et al. (2020) Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: a descriptive study. Chinese Medical Journal.

- 12 – Paraskevis et al. (2020) Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel corona virus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event. Infection, Genetics and Evolution.

- 13 – Benvenuto et al. (2020) The 2019‐new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution. Journal of Medical Virology.

- 14 – Wan et al. (2020) Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: An analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS. Journal of Virology.

- 15 – Huang et al. (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet.

- 16 – Zhang et al. (2020) Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak. Current Biology.