Incorrect: Contrary to the mechanism presented in the claim, osteoporosis is associated with a lower level of estrogen—not higher.

FULL CLAIM: Bones “are not made of calcium”; don’t use calcium supplements to treat osteoporosis; high estrogen is associated with osteoporosis ; wild yam is a treatment for osteoporosis

REVIEW

In July 2024, a snippet of a presentation by naturopath Barbara O’Neill circulated on Facebook where she advocated against using calcium supplements to treat osteoporosis. O’Neill justified her statement by claiming that bones “are not made of calcium”. Instead, she recommended the use of “Anna’s wild yam cream”, which would allegedly “lift the progesterone levels” and foster new bone formation.

O’Neill has a track record of health misinformation that Science Feedback addressed several times.

In 2019, the New South Wales Health Care Complaints Commission (HCCC) permanently banned her from providing any health services in Australia. This prohibition followed an HCCC investigation that revealed O’Neill actively discouraged the use of antibiotics, vaccinations, and proven treatments for cancer.

In their statement, the HCCC highlighted that O’Neill was an unregistered practitioner who lacked any recognized health-related credentials. The commission concluded that her advice posed a significant risk to public health and safety.

Like O’Neill’s previous claims, her claims on the role of calcium in bone formation and osteoporosis treatment are inaccurate. We explain more in the following sections.

Calcium is a key component of bones

O’Neill claimed that bones are “made of twelve minerals” that she listed, including elements like potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Although she included calcium in the list, she concluded that “[bones] are not made of calcium”.

Her claim is highly misleading. Although bones aren’t purely made of calcium, it’s an important component of bones and a key ingredient for new bone formation. In fact, 98% of the body’s total calcium is stored in bones, and calcium represents 34% of the weight of our skeleton[1].

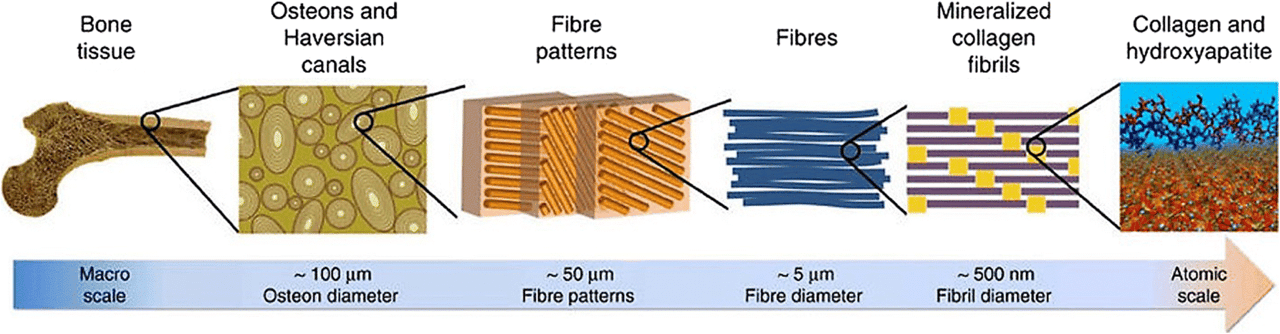

Bone tissue is mostly composed of a mineralized extracellular matrix (Figure 1). This matrix is a mix of proteins, such as collagen, and minerals. The main mineral ingredient is hydroxyapatite, which is made of calcium, phosphorus, oxygen, and hydrogen[1]. Hydroxyapatite is what lends bone its mechanical strength.

Figure 1 – Structure of bone at different scales. Note that the extracellular matrix is made of mineralized collagen fibers. The mineral component is mostly composed of hydroxyapatite crystals, which contain calcium and phosphorus. Source: Jeong et al.[1].

During bone formation, specialized cells called osteoblasts begin by laying out a scaffold of collagen fibers. They then deposit ions of phosphorus and calcium that crystallize into hydroxyapatite[2]. The deposition of calcium and phosphate and their crystallization progressively solidifies the extracellular matrix and turns it into bone.

Throughout our lives, our bones go through a recycling process: other specialized cells called osteoclasts degrade the old bone, and the ingredients are reused by osteoblasts to build fresh bone. Thus, a delicate balance between osteoblast and osteoclast activity is critical to maintaining healthy bone tissue throughout one’s lifetime.

In summary, not only is calcium an important component of bones, but it’s also an essential ingredient for building new bones. This fact directly contradicts O’Neill’s claim.

A diet poor in calcium increases the risk of osteoporosis

O’Neill also claimed that increasing calcium consumption is ineffective at preventing osteoporosis, arguing that “in aged care, all the old people are on calcium supplements and they’ve all got osteoporosis”. Once again, this is inaccurate.

Losing bone density naturally occurs with age. Osteoporosis is a condition where bones lost so much density that it becomes brittle. It’s described as a “silent disease” because it remains asymptomatic for a long time, until the first bone fractures occur. This is a fairly common condition. In the U.S., an estimated half of all women and a quarter of all men develop osteoporosis at some point in their lives.

At the cellular level, osteoporosis results from an imbalance in the bone recycling process described in the previous section, so that the old bone destroyed by osteoclasts isn’t replaced by new bone from osteoblasts.

There are several risk factors associated with osteoporosis, such as age, gender, family history, alcohol and tobacco consumption, sedentary lifestyle, and a vitamin D- and calcium-deficient diet.

The U.S. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases as well as the U.K. National Health Service both recommend a balanced diet including calcium- and vitamin D-rich food to fight against osteoporosis, contrary to O’Neill’s suggestion. For those who don’t get enough calcium in their diet, they recommend calcium supplements.

“Anna’s wild yam cream” isn’t a proven treatment for osteoporosis

O’Neill also asserted that a product called Anna’s Wild Yam Cream could treat osteoporosis by increasing progesterone levels. She claimed that progesterone stimulates osteoblasts, and that osteoporosis results from elevated estrogen levels that reduce the progesterone levels.

However, this is an incorrect description of the hormonal regulation of bone formation. Indeed, osteoporosis is associated with lower levels of estrogen, not higher. Mount Sinai explained that “estrogen (with or without progesterone) boosts bone density and reduces the risk of fracture by slowing bone loss, boosting the body’s ability to absorb calcium”.

In fact, estrogen/progesterone replacement therapy is one of the possible treatments for osteoporosis.

Wild yam (Dioscorea villosa) is marketed as providing relief from menopausal symptoms—menopause being a period during which estrogen and progesterone levels naturally fall—although its efficacy at providing said relief was only evaluated in a few small studies that produced mixed results.

Wild yam doesn’t contain progesterone, but its use in treating menopausal symptoms may have to do with its diosgenin content. Diosgenin is a chemical that mimics animal estrogen and progesterone. Researchers have been able to convert diosgenin into active steroid compounds in the lab. However, there is no evidence that diosgenin can be converted into progesterone in the body nor evidence supporting the claim that wild yam can treat osteoporosis.

Conclusion

O’Neill provided an inaccurate explanation of how bones are formed and maintained throughout life. Contrary to her claim, calcium is an essential component of bones. Not consuming enough calcium is one of the risk factors that can jeopardize bone formation and lead to osteoporosis. Contrary to O’Neill’s claim, adopting a diet with more calcium is one of the first steps someone can take to prevent or slow down osteoporosis. Wild yam isn’t a proven treatment for osteoporosis, and there is no evidence that it can cause an increase in progesterone.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Jeong et al. (2019) Bioactive calcium phosphate materials and applications in bone regeneration. Biomaterials Research.

- 2 – Blair et al. (2017) Osteoblast Differentiation and Bone Matrix Formation In Vivo and In Vitro. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews.