FULL CLAIM: “Covid death rates are higher among Republicans than Democrats, mounting evidence shows”; “Lower vaccination rates among Republicans could explain the partisan gap, but some researchers say mask use and social distancing were bigger factors.”

REVIEW

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers and journalists have noted partisan differences in adherence to physical distancing and mask wearing, and intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine between Democrats and Republicans in the U.S[1].

Now, one study by Sehgal et al. and one working paper (not peer-reviewed) by Wallace et al., both published in 2022, suggest that these divides have real-world consequences, with Republicans experiencing higher rates of COVID-19 death than Democrats[2,3]. Both papers were covered in multiple news outlets including NBC, The Intercept, Scientific American, and The Washington Post, which highlight the partisan gap in COVID-19 mortality.

Previous research on political partisanship and adherence to COVID-19 prevention strategies had already noted that these could lead to differences in health outcomes. One 2020 study by Gollwitzer et al., for instance, used geotracking data from 3,025 U.S. counties between March and May 2020 and found that counties with more Donald Trump voters compared to Hillary Clinton voters in the 2016 U.S. election were less likely to physically distance[1].

The study by Gollwitzer et al. also found that physical distancing was more strongly linked to political partisanship compared to other factors—including the number of COVID-19 cases in the county—and that less physical distancing was associated with higher numbers of COVID-19 infections and deaths in pro-Trump counties.

The study mentioned above was published in November 2020, before the COVID-19 vaccines became available in the U.S. COVID-19 vaccination has, like masking and physical distancing, become a partisan issue in the U.S.; polling done by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation, for instance, “found that political partisanship is a stronger national predictor of vaccination than other demographic factors”.

The COVID-19 vaccines approved in the U.S. are safe and life-saving, decreasing the risk of COVID-19 hospitalization, long COVID and death. Considering the gap in vaccination rates—91% of Democrats had received at least one shot compared to 60% of Republicans according to data research from December 2021 by the New York Times—it makes sense to ask whether this has caused differences in COVID-19 deaths rates between Republicans and Democrats. This is a question that both the study by Sehgal et al. and the working paper by Wallace et al. explore.

Two studies found partisan gaps in COVID-19 deaths

In the study by Sehgal et al. published in the journal Health Affairs in June 2022, the authors used COVID-19 mortality data from 3,109 U.S. counties. These counties were divided into four categories depending on their voting patterns in the 2020 presidential election: Republican, Republican-leaning, Democrat-leaning, and Democrat[2].

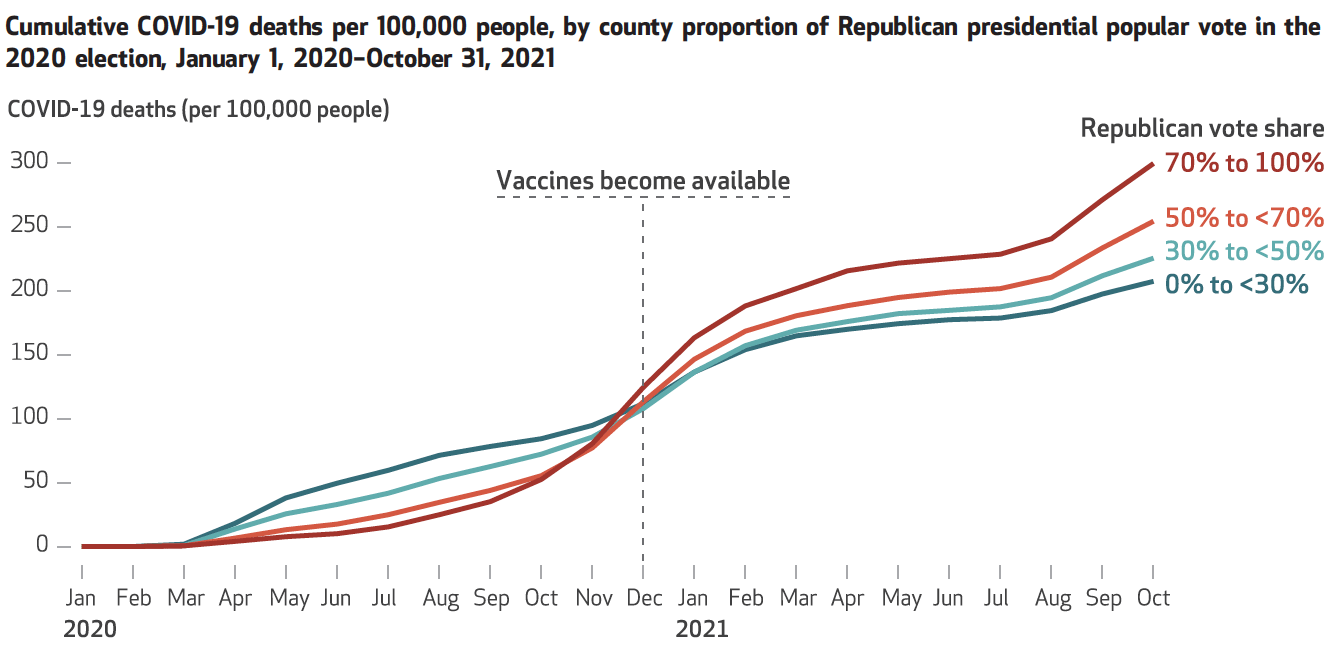

The study covered a period of time that stretched from 1 January 2020 to 31 October 2022, and observed that for most of the first year of the pandemic, Democrat and Democrat-leaning counties had a higher COVID-19 death rate. This trend began to narrow and eventually flipped in November 2020, shortly before the COVID-19 vaccines became available (Figure 1). By April 2021, Republican counties had a significantly higher COVID-19 death rate than Democratic counties, with this difference only widening over time.

Figure 1. In the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, per capita mortality in Democrat-leaning and Democrat counties exceeded that of Republican-leaning and Republican counties. This trend narrowed and then flipped in December 2020, with per capita COVID-19 mortality exceeding in Republican and Republican-leading counties thereafter[2].

When the authors controlled for state-level factors, such as COVID-19-related policies, they found that during the entire study period, the average cumulative number of COVID-19 deaths was 72.9 deaths higher per 100,000 people in Republican counties compared to Democratic counties. It’s important to note that, because the study looked at deaths at the county level, it cannot determine the political leanings of the individuals who died of COVID-19. But it does show that individuals living in counties with majority Republican voters are dying from COVID-19 at higher rates.

Many different factors including mask-wearing, physical distancing, and COVID-19 vaccine uptake, could explain the widening gap in COVID-19 death rates between Democrats and Republicans. Since the gap widened in 2021, when the vaccines were available, one might posit that vaccine uptake was the factor leading to this gap. But this isn’t the case.

“COVID-19 vaccine uptake only explained 10% of the difference in mortality between red and blue counties,” said Neil J. Sehgal, a public health professor at the University of Maryland (UMD) and one of the authors of the study, in a UMD press release about the paper. This suggests that rather than a single factor (vaccine uptake), a mix of factors, such as compliance with public health measures and engaging in risky behaviors, are driving this difference in COVID-19 mortality rates.

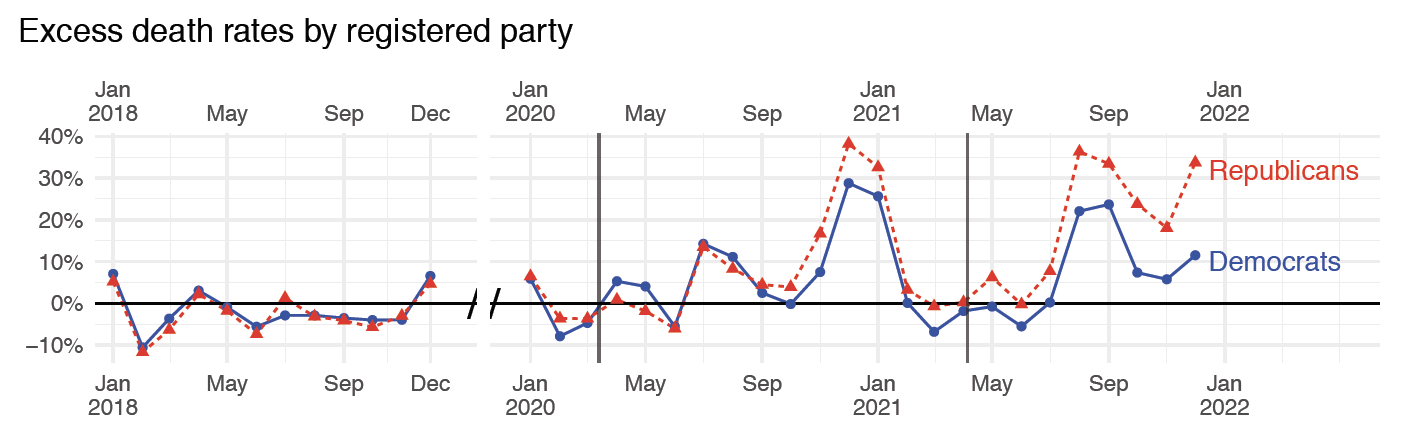

A working paper by Wallace et al. and published by the research nonprofit National Bureau of Economic Research in September 2022, adds further evidence that political partisanship impacts COVID-19 mortality risk[3]. This paper estimated the rates of excess deaths from COVID-19, finding that they were substantially higher among registered Republicans compared to registered Democrats. Excess deaths, also called excess mortality, represent deaths during a given time period that are higher than the usual number of deaths expected under normal conditions. This Insight article by Health Feedback explains the concept of excess mortality in more detail.

Working with 577,659 deaths in Ohio and Florida between January 2018 and December 2021, the authors linked these to 2017 voter registrations. They found that while in the early months of 2020, rates of excess death were similar between Republicans and Democrats, a gap soon began to form, with the Republican excess death rate nearly doubling that of Democrats in the summer of 2021 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Monthly excess death rates in Florida and Ohio plotted over time, stratified by registered party. Pre-pandemic and in the first months of the pandemic in 2020, excess death rates between registered Democrats and Republicans were similar, and members of both parties experienced a spike in excess death rates in the winter of 2020/2021. A sustained gap in excess death rates, however, began in the summer of 2021, and widened as 2021 progressed[3].

During the entire study period, Wallace et al. found that the average excess death rate was 76% higher among Republicans compared to Democrats. The difference was even higher after April 2021 when all adults in both Florida and Ohio were eligible for the COVID-19 vaccines: 153%. For the researchers, this “suggests that vaccine take-up likely played an important role” in the large gap in excess death rates between Republicans and Democrats.

When Wallace et al. looked at the relationship between this Republican-Democrat gap in excess death and county-level vaccination rates, they found that the association between the two only became significant after COVID-19 vaccines became widely available. Moreover, these differences were concentrated in counties where vaccination rates were lower. “In counties where a large share of the population is getting vaccinated, we see a much smaller gap between Republicans and Democrats,” Jacob Wallace, a professor of public health at Yale University and one of the authors of the working paper, told NBC News.

For Ashley Fox, a professor and global health policy specialist at University at Albany, SUNY, who was not involved in either study, the two studies “offer very compelling, complementary evidence of the effects of partisanship on COVID-19 mortality.”

In an email to Health Feedback, Fox explained that this is because both papers were “carefully done analyses that are able to adjust for residual confounding” and that “their findings are quite consistent in spite of the different approaches and data sources”.

This doesn’t mean the studies are without limitations. The paper by Sehgal et al. looked at COVID-19 mortality at the county level—rather than the individual level—and while the working paper by Wallace et al. does have individual-level data for both deaths and voting records, it relies on county-level vaccination data and is limited to two states (Florida and Ohio).

Fox also highlighted that the working paper would have benefited from looking at excess death rates among Independents. Studies about partisan differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and social mobility that included Independents found that this political group falls somewhere in between Republicans and Democrats[4,5].

For Fox, while the use of vote share is a reasonable proxy for partisanship, it “doesn’t help us to understand much about how partisanship affects outcomes”. Both studies provide evidence that partisanship impacts COVID-19 health outcomes, but neither explores mechanisms through which partisanship is shaping compliance with COVID-19 prevention strategies, Fox explained.

The studies also don’t “answer the broader question of why the pandemic became polarized in the way that it did and what is driving the polarization,” wrote Fox, who mentioned that partisan framing, targeted misinformation, and low and declining trust in institutions among political conservatives are all potential factors.

Partisanship has influenced health behaviors even before COVID-19

Taken together, both the study by Sehgal et al. and the working paper by Wallace et al. on COVID-19 mortality and political partisanship provide strong evidence that in the U.S. there’s a political divide over who or where one is at a higher risk of dying of COVID-19. According to epidemiological evidence, however, the mortality gap between Republicans and Democrats, has been growing for the last two decades, even before the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020.

In a 18 July 2022 piece in Scientific American, science journalist Lydia Denworth reported that while mortality rates had decreased between 2001 and 2019 in the U.S., this improvement was twice as large in Democratic counties (22%) compared to Republican counties (11%). These numbers come from a study by Warraich et al. published in June 2022 that looked at the mortality rates for the top 10 leading causes of death, such as heart disease and cancer[6].

The study found that between 2001 and 2019, the mortality gap between Democrats and Republicans increased for nine of the ten causes. In an editorial about the study and the impact of politics on health, Steven Woolf, a population health professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, explained that “life expectancy began to diverge dramatically across US states in the 1990s,” increasing in Democratic states with progressive policies and stagnating and even decreasing in more conservative states with Republican majorities.

While political partisanship has been impacting health outcomes for decades in the U.S., the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have placed this influence on hyperdrive, with Democrat and Republican states differing in terms of adopted policies and the timing of adoption. A 2021 study from the University of Washington, for instance, found that the most important predictor of when a state adopted indoor mask mandates was the presence of a Republican governor, with the adoption being delayed 98 days on average[7].

Perhaps no other COVID-19 policy has faced as much hostility from certain Republican governors as vaccine mandates, despite ample evidence that the COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective and that vaccine mandates are effective at promoting vaccinations. For instance, in October 2011, Texas governor Greg Abbott issued an executive order that banned any entity, including private businesses, from enforcing a COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

Beyond differences in state-level policies, Republican and Democrat voters themselves differed in their compliance with COVID-19 prevention measures, such as physical distancing and mask-wearing, and COVID-19 vaccination.

The research done by Sehgal et al. and Wallace et al. both found that COVID-19 mortality is higher in Republican counties and among Republican voters (in Florida and Ohio), compared to Democratic counties and Democrats, respectively. Both groups also found that this gap in mortality grew larger as the COVID-19 vaccines became widely available in 2021. While both studies point to the impact of vaccines, Sehgal et al. calculated that vaccine uptake explained only about 10% of COVID-19 mortality differences with other factors, such as compliance with public health measures and engaging in risky behaviors, explaining the rest.

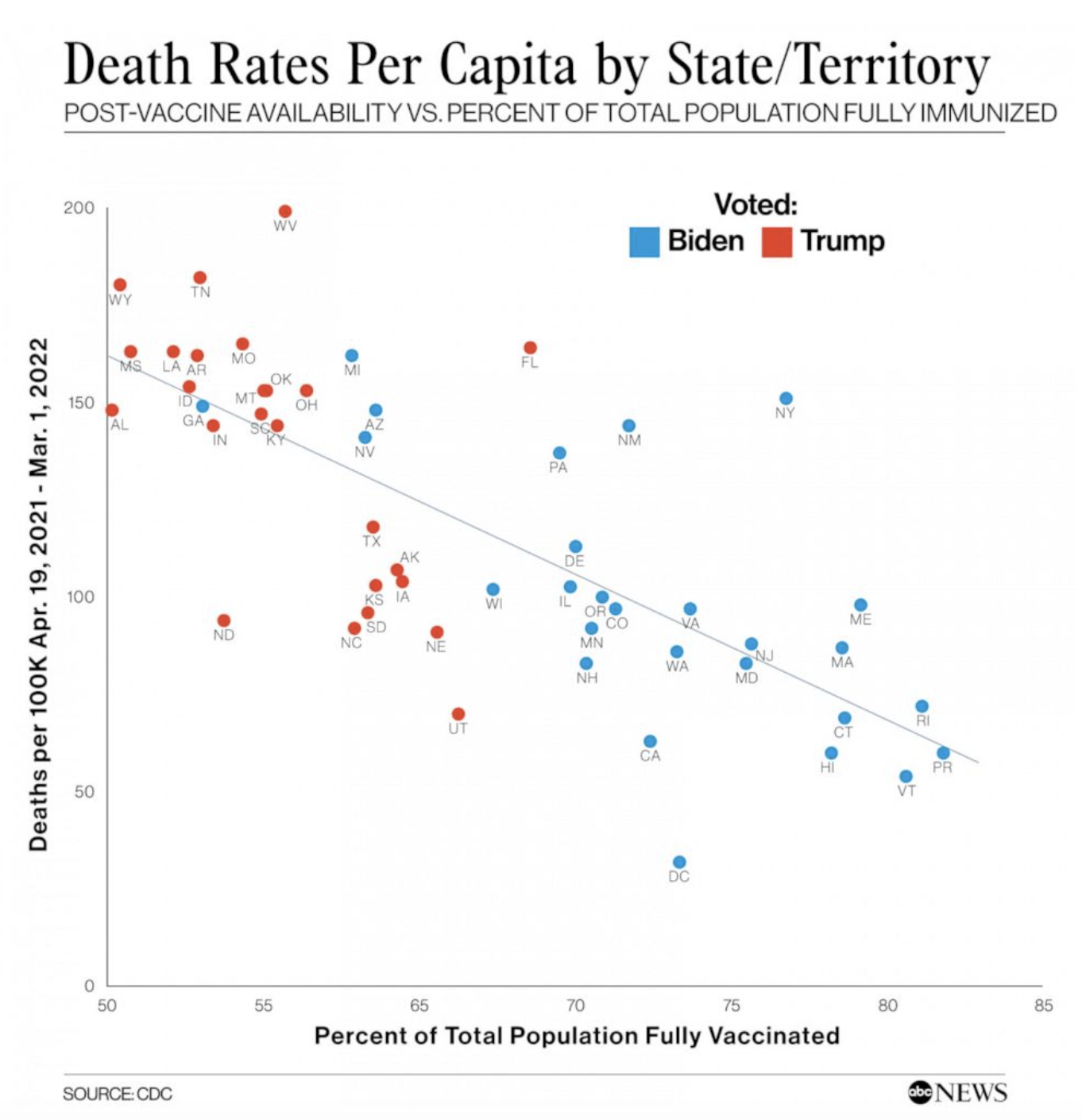

Complementing these two studies is an analysis of COVID-19 death rates in U.S. states and territories between 19 April 2021 and 1 March 2022 done by ABC News. The analysis found that there was a marked difference in the vaccination rates of states that voted for former president Donald Trump and those that voted for current president Joe Biden in the 2020 U.S. elections (Figure 3).

“[T]he 10 states with the highest vaccination rates all voted for Biden in 2020, while nine of the 10 states with the lowest vaccination rates voted for Trump,” explained journalist Arielle Mitropoulos. When cumulative COVID-19 data was added to the analysis, ABC News found that the political polarization of vaccine coverage could be plausibly linked to serious health outcomes: “[I]n the 10 states with the lowest percentage of full vaccinations, death rates were almost twice as high as that of states with the highest vaccination rates”.

Figure 3. An analysis by ABC News found that states that voted for Joe Biden in the 2020 elections had higher rates of vaccination compared to states that voted for Donald Trump, with a few exceptions like Georgia (GA). The analysis also found a trend between vaccination rates and COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 individuals, with states with the highest vaccination rates experiencing lower COVID-19 death rates. Source: ABC News.

As Seth Masket, a professor of political science at the University of Denver, told ABC News: “There are a few reasons why we’re seeing such differences in death and vaccination rates. The obvious one is that both vaccinations and other forms of COVID-19 mitigation have become heavily partisan.”

Together, the two studies suggest that COVID-19 mortality is higher among Republicans compared to Democrats, and that vaccination rates are an important factor—but not the only factor—behind this mortality gap. As such, political partisanship appears to impact COVID-19 health outcomes, although what drives this partisanship difference in compliance is not fully understood, though as Fox and other researchers have noted that targeted misinformation, distrust in scientists and institutions among Republicans, and other factors could all play a role

SCIENTISTS’ FEEDBACK

Ashley Fox, Associate Professor, University at Albany, SUNY:

Overall, I believe they offer very compelling (complementary) evidence on the effects of partisanship on COVID-19 mortality for the following reasons:

- They are both carefully done analyses that are able to adjust for residual confounding. While the Sehgal et al out of necessity relies on county estimates, the Wallace et al is able to make use of individual level data (though necessarily individual-level covariates). Their findings are quite consistent in spite of the different approaches and data sources. Both find that the partisan gaps especially widened after vaccines became available.

Sehgal et al.

- Strengths:

- Adjusts for chronic disease burden/comorbidities associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes. I haven’t seen previous analyses that look at partisanship control for this and I have considered this to be a major blindspot. We see surprisingly from their results that the risk differences for comorbidities is much smaller than the risk differences for Republic leaning and Republican counties (Exhibit 3). This was surprising to me- I thought comorbidities would soak up more of the effect, although perhaps social vulnerability is soaking up some of that.

- They have thought carefully about their selection of mortality data. COVID-19 deaths are more reliable than cases though not without their own problems.

- Vote-share Republican (Trump) is a reasonable proxy for partisanship

- Weaknesses:

- County-level data (potential ecologic fallacy- though this is mitigated by controls)

- Can’t distinguish mechanisms through which partisanship shapes compliance (and is partisanship or populism?).

Wallace et al.

- Strengths:

- Individual level data- matches death records with voter rolls (limits ecologic fallacy)

- Weaknesses

- Excludes non-voters?

- Would be good to look at Independents.

- Does not have individual-level data on behaviors/vaccine uptake

- Only two states

- Can’t distinguish mechanisms through which partisanship shapes compliance

Both use vote share (essentially for Donald Trump) as a proxy for partisanship. I think this is reasonable, but it doesn’t help us to understand much about how partisanship affects outcomes. Yes, through compliance, but it doesn’t answer the broader question of why the pandemic became polarized in the way that it did and what is driving the polarization- i.e., partisan framing, targeted misinformation, low and declining trust in institutions among political conservatives, the way the pandemic started on the coasts, etc.

Overall I was surprised at the strength of the findings in both. While my own research had shown partisan differences in compliance with public health measures including vaccination, I didn’t think that would translate so strongly into mortality. It was also quite striking (though not as surprising to me) how much vaccine uptake appeared to make a difference- both found little difference earlier in the pandemic when vigilance was higher across the board.

My own view (though I recognize not being solicited here) is that we should continue to double-down on vaccine mandates though relax all other measures, which are unnecessarily constraining if vaccination rates are sufficiently high.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Gollwitzer et al. (2020) Partisan differences in physical distancing are linked to health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour.

- 2 – Sehgal et al. (2022) The Association Between COVID-19 Mortality and the Country-Level Partisan Divide in the United States. Health Affairs.

- 3 – Wallace et al. (2022) Excess Death Rates for Republicans and Democrats During the COVID-19 Pandemic. NBER. [Note: This is a working paper and hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed at the time of writing.]

- 4 – Cowan et al. (2021) COVD-19 vaccine hesitancy is the new terrain for political division among Americans. Socius.

- 5 – Clinton et al. (2021) Partisan pandemic: How partisanship and public health concerns affect individuals’ social mobility during COVID-19. Science Advances.

- 6 – Warraich et al. (2022) Political environment and mortality rates in the United States, 2001-19: population based cross sectional analysis. British Medical Journal.

- 7 – Adolph et al. (2021) Governor partisanship explains the adoption of statewide mask mandates in response to COVID-19. State Politics and Policy Quarterly.