Misrepresents source: The fact that vaccine package inserts state a vaccine hasn’t been tested for carcinogenicity or mutagenicity doesn’t mean we have no data on whether vaccines cause cancer. Such tests weren’t performed because the safety of these vaccines had already been demonstrated through data acquired earlier, and vaccine ingredients aren’t present in quantities that pose a cancer risk.

FULL CLAIM: “There is not a single doctor in the world that can tell you that vaccines do not cause cancer. On every single FDA insert for every vaccine, there is a disclaimer of sorts which states that the vaccine has not been tested for carcinogenic or mutagenic effect [...] An explosion of childhood cancers (particularly leukemia) coincides with the explosion of vaccines after manufacturers were removed from liability [...] Big Pharma knows that among other things, vaccines can cause childhood cancers.”

REVIEW

In January 2024, political commentator and talk show host Candace Owens posted a tweet on X (formerly Twitter) claiming that vaccine package inserts state vaccines haven’t been tested for carcinogenic or mutagenic effect, that there has been an “explosion” of childhood cancers after manufacturers were removed from liability, and that “vaccines can cause childhood cancers”.

The tweet received more than 23,000 likes and more than 1.5 million views on X/Twitter.

A day earlier, Owens quote-tweeted a post by German disinformation outlet Disclose.TV, implicitly claiming COVID-19 vaccines cause cancer. The post was soon marked by X’s Community Notes, clarifying that the claim was implausible, since it was based on data collected before COVID-19 vaccines were made available. Owens has propagated health misinformation and conspiracy theories on several occasions in the past.

In this review, we show that epidemiological data on cancer in the U.S. don’t substantiate her claims and published studies so far haven’t found a convincing association between childhood vaccination and cancer risk.

Cancer trends have been on the rise for the last five decades, but reasons are multifactorial and don’t involve vaccines

Was there an “explosion” of childhood cancers after vaccine manufacturers were “removed from liability”? Were vaccine manufacturers “removed from liability” in the first place?

Owens’ claim about vaccine manufacturers’ no longer being liable is likely a reference to the U.S. National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act, which is commonly, but incorrectly, understood to remove all liability from vaccine manufacturers for any harm arising from vaccines. As we explained in a previous review, the Act, which came into effect in 1986, doesn’t completely stop people from holding manufacturers liable for harms from vaccination.

In fact, multiple lawsuits have been filed against a vaccine manufacturer by the anti-vaccine organization Children’s Health Defense, clearly demonstrating the falsity of this claim.

As for Owens’ claim that there was an “explosion” of childhood cancers after the Act was passed, we can verify it using epidemiological data about cancer in the U.S. One source for this data is the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.

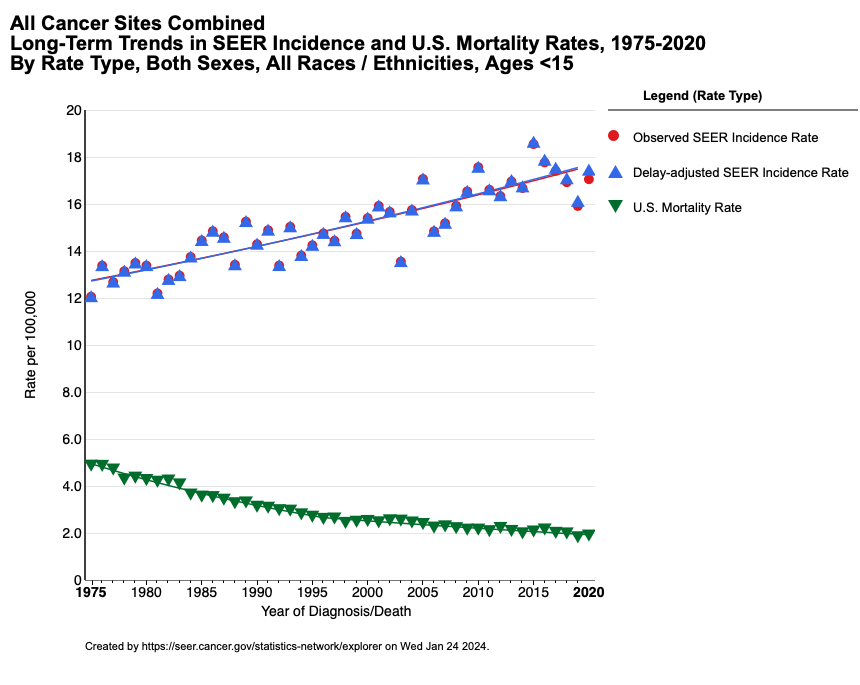

The data for trends in new cancer cases in those younger than 15 is shown below (see Figure 1). The data extends all the way to 1975, covering the periods before and after the Act came into effect in 1986.

Figure 1 – Long-term trends (1975 to 2020) in the incidence of all cancers in the U.S. in people younger than 15 years old (blue). The U.S. cancer mortality rate for the same age group is also shown (green). Source: SEER. Data retrieved on 24 January 2024.

The SEER data shows that cancer incidence rates have been rising since 1975, with no discernible difference before and after 1986. We can see that the rise is steady and gradual over time, with no sudden marked increases.

Thus the SEER data doesn’t paint a picture of an “explosion of childhood cancer” that Owens asserted had happened. Encouragingly, while incidence rates have risen, the cancer mortality rates for this age group have fallen, showing that cancer patients’ chances for survival have improved with time.

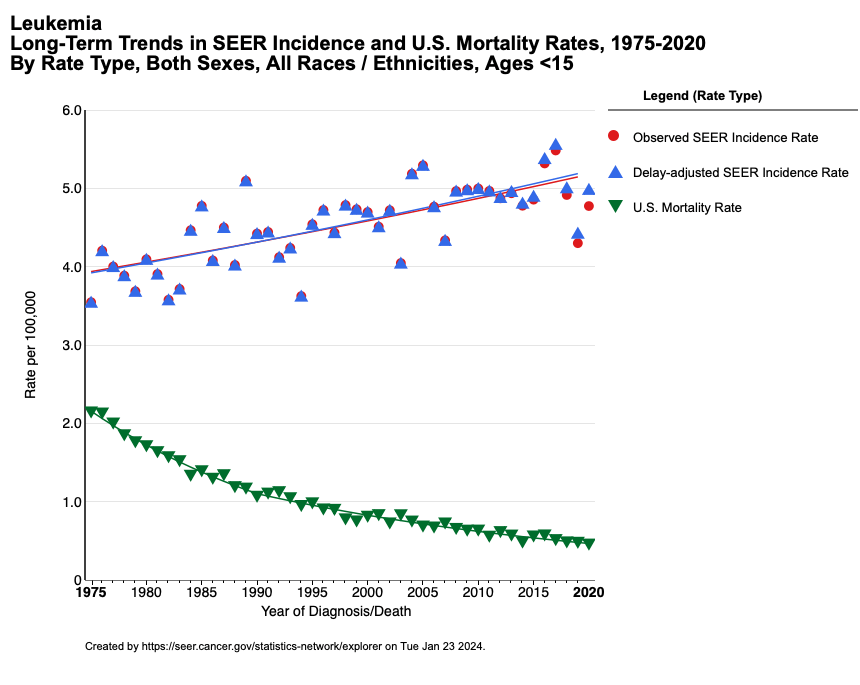

The same trend of a steady and gradual increase in incidence over time can also be seen in the case of leukemia (see Figure 2 below), which Owens’ tweet singled out. Leukemia, which is a cancer of the white blood cells, is the most common childhood cancer in the U.S. and globally, and is also the most commonly recorded cause of cancer death in children.

Figure 2 – Long-term trends (1975 to 2020) in the incidence of leukemia in the U.S. in people younger than 15 years old. The U.S. cancer mortality rate for the same age group is also shown (green). Source: SEER. Data retrieved on 23 January 2024.

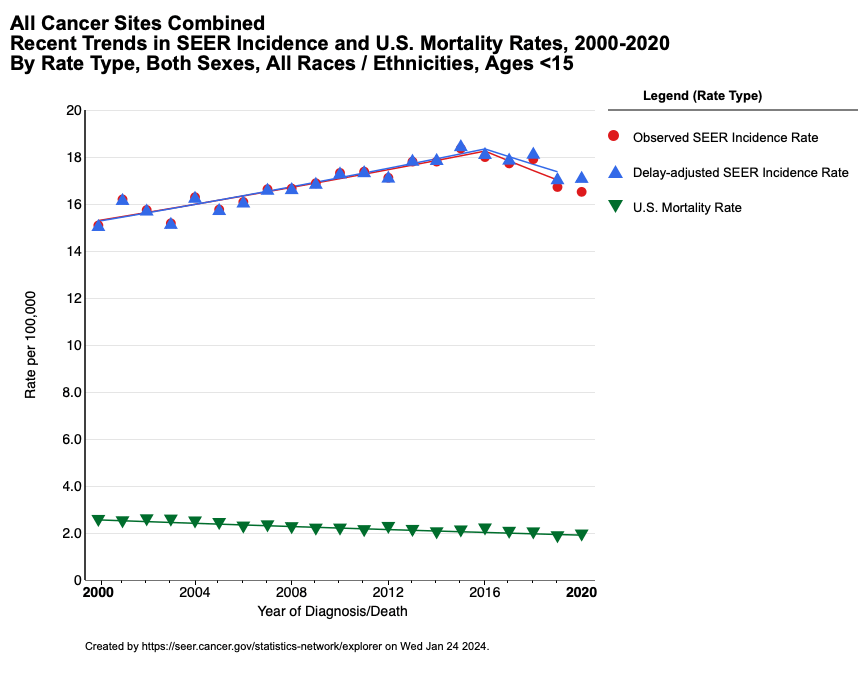

Interestingly, when we switch to looking at more recent trends, which look at the last two decades, as opposed to the trends for the past four decades, we see that the incidence for all cancers in the same age group starting from 2017 has been on a downward trend (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3 – Recent trends (2000 to 2020) in the incidence of all cancers in the U.S. in people younger than 15 years old (blue and red). The U.S. mortality rate for all cancers in this group is also shown (green). Source: SEER. Data retrieved on 24 January 2024.

Apart from SEER, we can also look at data from other credible sources. A published study by researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examined trends in childhood cancer in the U.S. between 2003 and 2019[1]. This study used data from U.S. Cancer Statistics, which covers all 50 U.S. States and the District of Columbia, in contrast to SEER, which currently covers fewer areas—22 U.S. geographic areas, to be precise.

This study reported a rise in the incidence rate of childhood cancer diagnoses, particularly for leukemia, lymphoma, liver cancer, bone cancer, and thyroid cancer. It also delved into potential reasons for the increased incidence rates:

“The reasons for increasing rates of pediatric cancer overall are likely multifactorial. First, overall rates of cancer may have increased because of changes in cancer reporting over the past 2 decades, such as the increased use of electronic pathology reporting to cancer registries […] Some increases or decreases in pediatric cancer rates could be secondary to changing trends in cancer risk factors related to preconception and pregnancy (eg, smoking, assisted reproductive technology), birth (eg, increasing maternal age, low birth weight), or childhood and adolescent life (eg, infection exposure, residential chemicals, radiation exposure, use of sunscreen).”

To sum up, the researchers thought that the increase in cancer incidence rates could be explained by changes in the way that different cancers are diagnosed and reported, as well as changes in exposure to various risk factors, for example increasing maternal age and residual chemicals.

Another study that examined U.S. cancer trends in adolescents and young adults postulated that environmental factors, dietary and obesity trends, and changes in screening practices are some major reasons for the increasing rate of cancer in that particular age group from 1973 to 2015[2].

Overall, Owens’ claim that vaccine manufacturers don’t bear any liability for their products is false, and the claim that there has been an “explosion” of childhood cancer isn’t substantiated by the data. Childhood cancer incidence rates have increased over the past four decades, but this increase has been gradual and steady, with no sudden marked increase. Researchers have considered several potential reasons for this, but they haven’t found that childhood vaccines are the cause, which we will speak more of later.

Vaccine package insert isn’t evidence that vaccines cause cancer

In her tweet, Owens offered vaccine package inserts as supporting evidence for her claim, citing the statement that vaccines haven’t been tested “for carcinogenic or mutagenic effect”, then went on to imply that no one has looked at whether there could be an association between childhood vaccines and cancer.

This form of argument, sometimes called “argument by vaccine insert”, involves cherry-picking information in a vaccine package insert, such as the adverse events listed in the insert, to make the case that vaccines are dangerous. This is despite the vaccine package insert also including an important caveat that adverse events aren’t necessarily caused by the vaccine, as one comic from The Logic of Science illustrates.

Like claims that cite adverse events in an insert as evidence of vaccine harms, Owens’ claim about the lack of carcinogenicity testing for vaccines is misleading and misrepresents the information presented in vaccine package inserts.

The website Skeptical Raptor, which debunks pseudoscientific claims, explained in this article that the package insert contains information that tells healthcare providers how a pharmaceutical product is to be used, and other information like warnings not to use a drug in certain situations.

In the U.S., regulations stipulate that all pharmaceutical package inserts—vaccines or no—must contain specific sections, including “Non-clinical toxicology”. This section describes the product’s potential for carcinogenesis (ability to cause cancer), mutagenesis (ability to produce mutations), and fertility impairment and is what Owens’ tweet refers to.

However, this section has “little applicability” in the case of vaccines, the Skeptical Raptor article pointed out, because studies over the long term have detected no indication that the vaccine causes cancer:

“The [package insert] may state some innocuous verbiage such as ‘no known information’ meaning that in the 10-15 years of research and study, no evidence that the vaccine is carcinogenic or mutagenic. This section is frequently misused by anti-vaccine pseudoscientists using the argument from ignorance – they think that because it hasn’t been tested for cancer, it could cause cancer. However, there are no biologically plausible mechanisms whereby vaccines could convincingly be linked to any cancer.”

Pediatrician Vincent Iannelli also tackled the same claim, explaining that established guidelines for nonclinical evaluation of vaccines generally don’t consider carcinogenicity or mutagenicity studies for vaccines to be necessary, because earlier findings don’t indicate the need for concern.

The second edition of the reference book A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Nonclinical Drug Development, published in 2016, states the following with regards to vaccines:

“Generally, mutagenicity studies are not required for vaccines (WHO guidelines on nonclinical evaluation of vaccine and European Medicines Evaluation Agency (EMEA)). Genotoxicity studies might not be relevant for adjuvant of biological origin. The potential for gene mutation, chromosome aberrations, and primary DNA damage might be needed for synthetic adjuvants, because they are considered to be new chemical entities.”

“Generally, carcinogenicity studies are not required for vaccines (WHO guidelines on nonclinical evaluation of vaccine and EMEA). This is because of the low dose and the low usage of the adjuvants, meaning that the risk of tumor induction is very small, according to EMEA guidelines.”

The EMEA guidelines cited in the book has since been replaced by the WHO guidelines published in 2005 (WHO guidelines on nonclinical evaluation of vaccines, Annex 1), in which the same reasoning still prevails:

“Genotoxicity studies are normally not needed for the final vaccine formulation. However, they may be required for particular vaccine components such as novel adjuvants and additives.”

“Carcinogenicity studies are not required for vaccine antigens. However, they may be required for particular vaccine components such as novel adjuvants and additives.”

Iannelli acknowledged that formaldehyde, which is present in some childhood vaccines, can lead to cancer. However, this effect is only observed in those who have been exposed to high levels of formaldehyde over prolonged periods of time, as in the case of occupational exposure.

Moreover, formaldehyde also occurs naturally in the human body as it is needed for DNA synthesis. And the quantity present in any individual vaccine is about 1,500 times smaller than the quantity present in a two-month-old infant. This means that there’s no plausible reason for the formaldehyde in vaccines to pose a safety concern.

To sum up, the reason why vaccine package inserts state that “the vaccine has not been tested for carcinogenic or mutagenic effect” is because there’s no scientific grounds to think the vaccine would cause either effect. Childhood vaccines don’t use novel adjuvants or additives and vaccine ingredients aren’t present in quantities that are expected to cause cancer, based on previous research.

Published studies haven’t found that childhood vaccines cause cancer

Owens’ claim implied that no scientific work had been done to investigate whether childhood vaccines could influence cancer risk, but this isn’t true. Below are some of the studies we found that explored this question.

A 1997 case-control study in Greece compared 153 hospitalized children who were diagnosed with leukemia (cases) with 300 hospitalized children who didn’t have leukemia (controls)[3]. The study found no statistically significant association between leukemia in childhood and the number of viral vaccines received (defined in the study as measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B vaccines), or with the number of DTP (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis vaccine) vaccines received.

In 1999, researchers published a case-control study performed in New Zealand, also looking at whether various factors, including vaccination, could be associated with childhood leukemia[4]. It included children aged between 0 to 14 years old. The researchers reported that “[t]here was no significant trend with the number of different vaccinations”.

A study published in 2005 in the International Journal of Epidemiology, also another case-control study, compared children who had been diagnosed with leukemia and those who didn’t[5]. Examining vaccination records in northern California, the researchers found no association between childhood leukemia and the vaccines against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles, mumps, and rubella.

A systematic review and meta-analysis (a type of study that pools together the results of multiple studies addressing the same question for analysis) published in Scientific Reports in 2017 didn’t find an association between early childhood vaccination and a greater risk of childhood cancer[6]. In fact, the researchers found that vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of childhood cancer, although the authors advised caution in interpreting these results, stating these had to be replicated.

Readers will observe that none of the studies above are a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. While such an experimental design is, in theory, most ideal, ethical implications can limit its use. In the case of approved vaccines that have been established as effective, it’s considered unethical to keep children unvaccinated for the sake of having a control group, as this would leave the children exposed to the risk of vaccine-preventable diseases. As such, researchers use different approaches to answer this question.

Conclusion

Childhood vaccines typically don’t need to undergo testing for carcinogenicity and mutagenicity because their safety had already been demonstrated in earlier studies and because vaccine ingredients aren’t present in quantities that pose a safety risk. Published scientific studies so far haven’t found reliable evidence showing that childhood vaccination increases the risk of childhood cancer. In fact, some childhood vaccines, such as the Hepatitis B vaccine and the human papillomavirus vaccine, protect individuals from certain cancers.

REFERENCES

- 1 – Siegel et al. (2023) Counts, incidence rates, and trends of pediatric cancer in the United States, 2003-2019. Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

- 2 – Scott et al. (2020) Trends in Cancer Incidence in US Adolescents and Young Adults, 1973-2015. JAMA Network Open.

- 3 – Petridou et al. (1997) The risk profile of childhood leukaemia in Greece: a nationwide case-control study. British Journal of Cancer.

- 4 – Dockerty et al. (1999) Infections, vaccinations, and the risk of childhood leukaemia. British Journal of Cancer.

- 5 – Ma et al. (2005) Vaccination history and risk of childhood leukaemia. International Journal of Epidemiology.

- 6 – Morra et al. (2017) Early vaccination protects against childhood leukemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports.